- Home

- Hughes, Rhys

Link Arms with Toads!

Link Arms with Toads! Read online

Link Arms with Toads!

Link Arms with Toads!

Rhys Hughes

Whether you are a ghost, a robot or just an apeman, you can always link arms with toads!

Chômu Press

Link Arms with Toads!

by Rhys Hughes

Published by Chômu Press, MMXI

Link Arms with Toads! copyright © Rhys Hughes 2010

The right of Rhys Hughes to be identified as Author of this

Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Published in May 2011 by Chômu Press.

by arrangement with the author.

All rights reserved by the author.

First Kindle Edition

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Design and layout by: Bigeyebrow and Chômu Press

Character illustration by: Torso Vertical

E-mail: [email protected]

Internet: chomupress.com

A showcase of

Romanti-Cynical Stories

Dedicated to!

The beautiful, wonderful, marvellous,

superlative, incredible, delectable

and incomparable

Adele Whittle

“Rhys Hughes seems almost the sum of our planet’s literature... As well as being drunk on language and wild imagery, he is also sober on the essentials of thought. He has something of Mervyn Peake’s glorious invention, something of John Cowper Powys’s contemplative, almost disdainful existentialism, a sensuality, a relish, an addiction to the delicious. He’s as tricky as his own characters... He toys with convention. He makes the metaphysical political, the personal incredible and the comic hints at subtle pain. Few living fictioneers approach this chef’s sardonic confections, certainly not in English.”

Michael Moorcock

“Hughes’ world is a magical one, and his language is the most magical thing of all.”

T.E.D. Klein

“It’s a crime that Rhys Hughes is not as widely known as Italo Calvino and other writers of that stature. Brilliantly written and conceived, Hughes’ fiction has few parallels anywhere in the world. In some alternate universe with a better sense of justice, his work triumphantly parades across all bestseller lists.”

Jeff VanderMeer

Contents

1 The Troubadours of Perception

2 Number 13½

3 The Taste of the Moon

4 Lunarhampton

5 The Expanding Woman

6 All Shapes Are Cretans

7 The Innumerable Chambers of the Heart

8 Pity the Pendulum

9 333 and a Third

10 The Candid Slyness of Scurrility Forepaws

11 Ye Olde Resignation

12 Castle Cesare

13 The Mirror in the Looking Glass

14 Oh Ho!

15 Loneliness

16 Hell Toupée

17 Inside the Outline

18 Discrepancy

Afterword

Publishing History

Acknowledgements

About the Author

The Troubadours of Perception

Rosa is harsh and meaty, like an old glass of red wine. She wants to play duets in the dusky twilight. Alice is slow and cool, like a watermelon that takes several days to consume. She still has trouble tuning her instrument. Clara and Gabrielle wander the fretboard in the search for a fuller sound. I want to make love to Gabrielle but I am unsure of the fingering.

In the lounge of a pleasant suburban house in Solihull, I dally with Christine. The lamps are turned low, there is a real fire in the hearth. I bless the mirror above the mantelpiece that reflects my profile back at me. The shadow of an emerging beard, the long shiny hair that curls around my shoulders, the glittering of an earring. I have the accent down to perfection, the rascally shrug.

Christine is not really interested in the guitar. She wants to talk. She does not care that my own is strung with silver strings to give a sweeter sound. Her husband is away on a business trip. She suspects that he is losing enthusiasm for the relationship, that he has been bitten by the fleas of new desire. She has a similar itch, a need to be scratched. I tease, I croon, I softly sing. The fleas that tease in the high Pyrenees. O Christine!

Afterwards we sip coffee and I listen to an account of their early life together. It had all been fun then. Or had it? Her doubts are growing, they are beginning to encompass the past. I ask her how she sees her role within the shifting mores of a modern society. In all this time, a single note has she played. But my fees will be the same. I can humour the dabblers, the dilettantes, but I cannot afford to indulge them. It is my way of life.

The bedsheets are chill around Christine’s lithe body. Her musky scent reminds me of incense, honeysuckle, the taste of caramel. Candles float in little vases full of water. Her room is tastefully furnished, almost sparse. I trace delicate pathways along her stomach with my tongue. I used to teach the piano. I used to dream of possessing such women as Christine on the stool while our fingers explored their own crescendo. But I have learned from experience. Ivory and ebony keys do not turn locks of hearts; what is required are the chords that bind.

I leave Christine and catch the bus back into town. Dust and leaves swirl before me. I feel self-consciously romantic in my waistcoat, the white shirt whose huge flapping cuffs I must leave unbuttoned, face and hands never too clean. We trundle through streets dim and featureless to those who do not know. I have finally solved the enigma of these suburban boulevards, treeless avenues and bowbacked crescents. The language of the pavements is in my blood, my greasy veins. Behind each pair of William Morris curtains there are shattered fragments of secret lusts, shards of which have lodged in my heart.

Jessica presents a quite different prospect. There is a more subtle understanding between us. Her husband is possibly a little too devoted. It would be difficult for her to betray him without feeling guilt. Her frustration manifests itself in the sly look, the parted lips. She has become an expert in the ways of the flirt. Sometimes I think that I am imagining her responses, so skilfully does she proceed.

She also happens to be a very good player. With the possible exception of Catherine, she is my most talented pupil. It seems that soon there will be little more I can teach her. I will have to depart forever then, with only the taste of a lost chance to remember her by. She sings as she plays, and her voice is surprisingly homespun among the exotic artifacts of her living room, the indigo batiks, the wooden carvings and ethnic throws. Homespun from gold, her hair.

I correct her fingering in one place only and I do this by taking her hand. She wants to know what it is like out there, life on the pavement. Thrilling, dirty, absurd, I tell her. She is not quite enchanted but she is tempted to smile. I have seen her smile, I know that it is radiant, trembling, all that my own smile is not. My own smile is wicked and charming. Wickedly charming.

Jessica is on my mind a great deal of the time. So too Amelia, a direct descendant of the last man to fight a legal duel in England. The victor, I assume; I have never questioned her on this point. So Amelia needs no work, no flash of chipped incisor. She is already mine, became mine right from the beginning, though in one way only. Her bosom heaves. It is very gratifying to learn that she shares my passion for the poet, the only poet. Le ciel est triste et beau comme un grand reposoir. We watch the clouds part for long afternoon hours. Over the crumbling brick walls of her semi-detached garden, the clematis hugging tight to its lattic

e, the morning glory, the sun drowns in its vermilion.

Out again into the dusk. Amelia does not dance. Amelia prefers to languish in a curiously undramatic way. It is Isabella who likes to dance. I play her a valse and a saraband and she is stately, graceful, a little sad among the frosty adjuncts of the kitchen, where she always affects to have her lessons. I guess that only here the neighbours may spy on her. She is cultivating her reputation.

Isabella’s husband is a salesman, a surly fellow I once met and liked. But Isabella tells me that his manner is pure guile. He is contented with life, his cynicism is mere sophistication. He is also a devoted Adventist. His chosen method is to knock on doors, following much the same routes as myself, and to ask the occupants whether they would like to talk about God. Usually they say no. He then asks if he can sell them some double-glazing instead.

I watch Isabella stretch upwards, her eyes fixed on some remote point beyond the shelf of spice jars, her bare calves as smooth as a legato. I watch her weave between the oven and the washing machine. Later, when the mood takes her, she will sit on the latter during spin cycle while I watch with hooded eyes. The neighbours will make notes. Her paramour is a parvenu, they will say. A roguish fellow.

With Isabella I play old Spanish airs. With Lydia I tour the oeuvre of Guiraut Riquier, still a neglected composer. Lydia is an exception to one rule of my calling. She does not share the general acceptance of the grime any true romantic must carry on his boots. She insists I remove my footwear on her threshold. Toes wriggle in chilly anticipation. Will I ever bear her over another threshold? Will I ever hear her loosen her restraints with a shriek as piercing as a split harmonic? I am working on Lydia, practice is what it takes. Chapeaux bas!

Out on the pavements, weaving their own destiny, there are others like me. They are colleagues, rivals. I see them trailing their worn instruments in the dirt behind them. Our paths frequently cross. Over all the cities of the land, the suburbs, we are engaged in absorbing the fantasies of a million wives. Our travels are netting the happy hamlets, the conurbia of mock-Tudor ideals, the security of the scrubbed, the pools of quiet desperation with their shallow bathers. We are gouging the conduits of a freer life, evolving a whole nervous system down which emotions can flow like honeyed wine.

But it is not all certainty, this game of ours. The control can be lost easily enough. In the park, in winter, I often serenade the trees; an aubade to a false dawn. Hunched, cold, I neither welcome nor mock the sun. My fingers are like the highest twigs themselves, covered in sleet. The power slips between. Sometimes I meet my match, or more than my match. They are out there. No one who takes this profession seriously can be deceived for long. Many of them, innumerable.

I fear them. I fear their strength and their mystery. There is Madeleine, who likes to bounce me on her knee while I play. There is Yvette, who speaks not a word and hides behind widow’s weeds though her husband is very much alive, propped up in an old armchair, drooling, facing us as we trill. There is Arabella, who furnishes her house all in black and has set a worm-gnawed Grandfather clock in every room. There is Rebecca, who does not care for my silver strings. There is Melissa, who keeps a collection of love letters in a coffin in her attic. Her house is full of a delicate mist, cobwebs. There is Leonora, who I am at a loss to describe because she stays always behind me, always, no matter how fast I turn.

Helena is the one who disturbs me the most. I would like to break off our arrangement, I would like to depart from her and never return. But there is a hold, a morbid influence that she exerts on me. Her house is full of jars. I ask her what she keeps in them. She taps her nose and winks. Dreams, she replies; the dreams of all her past lovers. She collects the residue from her own generous thighs after she has toyed with them. I have not succumbed. I feel drained with Helena, enervated, sucked dry. It is only a matter of time.

Something else is happening. There have been developments. Hazel, who has been separated from her husband for nearly a year, persuades me to pay him a visit. His house lies on the other side of town. I find that he wants to pay for lessons as well. So I am able to listen to his side of the story. He knows all about my experiments with Hazel. It has reawakened his feelings, anger and deep love. They are reunited because of me. Then they break off contact. Music was the food of love, but now they are full. They are devoted. Who am I to protest?

This is happening to my colleagues and rivals, I hear. Many of them now have more male pupils than female. What can this mean? Will we be forced to work for money alone? Will they all abandon me, one by one? Barbara, Candida, Deborah, Eulalia, Fiona, Faustina, Gwyneth? What will happen to my soul, my essential nature? Will Rosa no longer want to play duets in the dusky twilight? Will Alice learn to tune her instrument without me? Will Clara and Gabrielle succeed in their quest for a fuller sound?

A crisis meeting is called between all members of our fraternity. We gather in a crumbling café in the metropolis, an establishment that has served our kind for generations. We fill the place to bursting. There are more players in this tarnished age of ours than listeners. There is talk of returning to the piano. But I do not want to lose my hair, my patience. I do not want to have to wear tiny round spectacles. Are there really no alternatives? There is talk of finding a use for men, of somehow fitting them into our worldview. But what use can I find for men? I am lonely, lonely. I am so lonely.

While we argue, debate, cajole, the waiter serves us all supper. We need to fortify ourselves for the tribulations ahead. But we must not be defiled. We are minstrels, the lyric poets of the garden cities. Music alone is the reason for our being, we require no other sustenance. In this particular café our needs are understood. Do not fret. We shall rebuild Carcassonne, we shall. Solemnly, in the sinister light that emanates from the charcoal ovens, we dine on manuscript stew and violin steaks and pick splinters from between our broken teeth.

(1994)

Number 13½

Among the Isles of Scilly, Tresco justifiably holds a high place. Not that any of the members of the archipelago should really be described as high, for at no point do they rise much above 100ft. Yet they are alluring enough to tempt the curio hunter, the seeker of solitude or the college refugee. Tresco in particular has nets enough to snare the incautious tourist – once the private estate of a priory, it retains a cloistered air; a privileged atmosphere that owes partly to its impressive ruins and partly to its absence of budget accommodation.

Travellers to the islands have a choice of braving the stormy seas between Penzance and the largest of the group, St. Mary’s, or of taking to the air for the brief flight to the small airport outside Hugh Town. There are few direct flights to Tresco and only one hotel to be found, the Island Hotel – expensive but all that can be desired. It is now run by a Swede, Wilhelm Magnus, who was shipwrecked on one of the beaches during an attempt to sail single-handed around the globe in a coracle. His account of the affair, Journal of a Scilly Billy, is a fair specimen of the class of books to which I have not yet alluded.

In the spring of 1997, two mainlanders arrived at this isolated place, in an attempt to assuage a peculiar kind of brain fever. They were both Birmingham men, academics from that greatly regarded bastion of learning, the Moseley College of Further Education. They were (it is certain) physicists currently engaged on certain researches into the nature of subatomic particles. We shall dignify their experiences by naming them Baring-Gould and Purnell. The former was much interested in the behaviour of photons; the latter detested photons and had time only for neutrinos. Yet they contrived somehow to remain good friends, even taking with good grace the insults each hurled on the other’s favourite elements, hydrogen and argon respectively.

One thing they did share and that was a fear of flying. Thus it was that on April 13th they braved the stormy seas beyond Land’s End in a leaky ferry, the Mezzotint, whose Italian Captain, Giovanni Paoli, had left his heart in England as a small boy. Baring-Gould sought relief from the buffeting waves on the highest

deck; Purnell was of a like stomach. Together they turned green and clutched to the rails for dear life. Captain Paoli solemnly announced over the tannoy that he had never witnessed a storm quite like it. As the huge black waves broke over the physicists, one of them turned to the other and hissed through trembling lips, “There are thirteen passengers aboard!”

It seemed an augur of evil. The previous night, while still in Penzance, Baring-Gould had sworn he heard the main church clock strike thirteen instead of twelve; and Purnell had eaten no less than that number of pieces of toast for breakfast. But though the vessel pitched and yawed ominously, it came to no grief. The Mezzotint docked safely in Hugh Town; the only concession to the fury of nature being that the three-hour journey had lasted seven and that the figurehead of the ferry had been consigned to the furnace when Captain Paoli had seen how low on fuel they had run. We shall discuss the number 13 and the importance of figureheads later. (There is a ghost in this story but it shall not be revealed until the very end.)

The travellers spent the rest of the day on St. Mary’s, recovering from their frightful experience. The following morning, the weather being more clement for such a venture, they took another boat to Tresco, landing at the southernmost point of Carn Near, a ten-minute walk from the entrance to the delightful Abbey Gardens. Here, amid the tumbled remains of the priory, are the impressive subtropical gardens, first laid out in 1834. Though many of the seeds hail from no further afield than Kew Gardens, some have their origins in Africa, South America and the Antipodes. You really should try to visit these gardens sometime, it may do you good. But I am not writing a guidebook.

Link Arms with Toads!

Link Arms with Toads! The Smell of Telescopes

The Smell of Telescopes The World Idiot

The World Idiot The Young Dictator

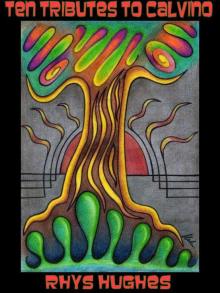

The Young Dictator Ten Tributes to Calvino

Ten Tributes to Calvino